Interview de Lior Inbar, historien et archiviste du Musée Beit Lohamei Haghetaot (Ghetto Fighters’ House – Musée des combattants de ghettos)

Galilée, le 19 février 2024

En chemin…

Pour illuminer le monde, il faut en soi

une flamme infatigablement incandescente.

Miriam Novitch, Membre du Kibbutz (1950)

Le Musée n’était d’après mes justes calculs qu’à quelques kilomètres de mon domicile. J’avais décidé de prendre le bus, ou plutôt les bus pour y parvenir. J’ignorais (comment l’oublier ?) que les bus israéliens roulent au-dessus de leurs roues et que l’on y est plus secoué que dans la Démone de Satanas et Diabolo. Une chaleur épouvantable, une route caillouteuse, le premier bus m’indique un arrêt, je descends. J’attends ! Nulle part, au milieu d’une route qui ressemble à un chemin que foulent des camions fous. J’attends encore, incapable d’identifier où diable je suis et ce que je vois. Le bus, après quelques autres qui ne s’arrêtent pas, vient. Je monte. Allez savoir si je suis dans le bon. En criant, car j’ai remarqué que les chauffeurs d’autobus israéliens ne vous informent jamais, ils vous engueulent ! Je descends. Pareillement, au milieu de ce qui m’apparaît comme nulle part. Au loin, un champ, une barrière. Un grand bâtiment. Cela doit être là. Je suis en Galilée, en basse Galilée. Le paysage semble s’étendre, respirer, il s’étire comme sous l’effet de perpétuels premiers rayons de lumières.

La Maison des combattants de ghettos se tient devant moi, vaste, infinie. On ne comprend pas comment,- mais il en est toujours ainsi en Israël, – on peut ainsi passer d’un état à un autre, si rapidement, d’une vision à son opposé, d’une perspective à un si vaste horizon si soudainement. Car, à l’instant, ce qui se tient devant moi ne ressemble à aucun autre paysage.

Je ne parlerai pas du Musée, ce que Lior Inbar, qui y travaille depuis 20 ans, fera avec une grande connaissance et intelligence, je veux simplement ajouter avant de commencer cette interview combien ce Musée n’a pas d’équivalent. D’avoir fréquenté nombre de lieux de mémoire sur la Shoah, dont bien sûr Yad Vashem, traînée au début par mon père tremblant, puis seule, tremblante à mon tour, j’eus la grande émotion de sortir de Beit Lohamei l’âme pleine, les yeux éblouis de fierté et d’espoir. Sur la terrasse construite sciemment au-dessus du Musée, -terrasse qui domine toute la Galilée, et qui s’ouvre sur le Kibboutz,- j’ai vu distinctement, sans la moindre ombre, sur cet horizon infini, cette vie juive. Irréductible.

Nous sommes aujourd’hui le 7 octobre. Comme tous les jours depuis ce maudit 7 octobre. Ce que la “Maison des combattants de ghettos” a transmis, n’a cessé de vouloir transmettre, doit être perpétué. Aujourd’hui encore, surtout aujourd’hui. Pour que demain, les jours puissent s’égrèner un à un, se construire minute après minute, regagnant leur rythme jusqu’aux rayons clairs des prochains Shabbat.

- Cher Lior Inbar, tout d’abord pouvez-vous expliquer en quelques mots la spécificité de votre Musée ? Et ce qui le différencie très nettement de Yad Vashem ?

La Maison des combattants de ghettos est une conception unique, voulue depuis sa création : elle a été fondée en avril 1949 lorsque le kibboutz Lohaemi HaGeta’ot s’est installé en Galilée occidentale. Cent cinquante jeunes survivants de l’Holocauste se sont unis pour construire une communauté et bâtir un avenir à leurs enfants, tout en établissant en parallèle un institut dédié à la mémoire, à la documentation, à l’éducation et la commémoration de l’Holocauste. La cérémonie d’inauguration du kibboutz s’est déroulée lors de l’Assemblée commémorative des six ans du soulèvement du ghetto de Varsovie. Parmi les fondateurs de ce kibboutz figuraient des leaders du soulèvement, comme, entre autres, le couple Zivia Lubetkin & Yitzhak (Antek) Zukerman. La création du musée Ghetto Fighters’ House a véritablement été un acte pionnier qui allait laisser son empreinte. En effet, ces combattants d’hier n’avaient pas attendu que le jeune État d’Israël prenne en charge la mémoire et la commémoration de l’Holocauste, mais en avaient eux-mêmes décidé la création et l’édification. Il faudra encore quelques années à l’État d’Israël pour établir le Musée de “Yad Vashem” à Jérusalem. La raison pour laquelle nos fondateurs ont choisi d’intituler un tel musée “Maison” ne relève pas d’un titre d’apparat, mais bien d’un choix fondamental : ils souhaitaient donner à tous les visiteurs un sentiment chaleureux de familiarité et de proximité. Le musée organise des expositions thématiques qui invitent et inspirent le visiteur à un dialogue, encourageant un échange éducatif, sollicitant un sens partagé, à partir de chaque visite, de chaque interrogation. C’est ainsi encore que nous percevons notre mission en tant que successeurs des fondateurs et c’est ce qui nous distingue de toute autre institution, y compris Yad Vashem.

- Quel est votre rôle ? A-t-il changé à mesure des années et de votre expérience ?

Je suis au départ professeur d’Histoire, en lycée. J’ai commencé, il y a maintenant presque vingt ans, à la Maison des combattants de ghettos en tant qu’instructeur. Après avoir obtenu ma maîtrise d’histoire, j’ai rejoint l’équipe des archives en tant que chercheur. À mesure des années, j’ai publié un nombre important d’articles académiques, sur la base des trésors incommensurables que recèlent nos archives. J’ai également été le rédacteur et directeur de l’Assemblée annuelle de la Journée commémorative de l’Holocauste, et je gérais le fonds de recherche de bourses du musée. Depuis plusieurs années, je m’occupe aussi du département de formation des enseignants.

L’année dernière, j’ai décidé de faire un doctorat, à l’université de Haïfa, – mes recherches portent sur les mouvements des kibboutzim après la guerre du Yom Kippour de 1973.

Avant ce samedi 7 octobre, la guerre de Yom Kippour était l’événement le plus tragique de l’histoire des kibboutzim. Hélas, mes recherches sont devenues, soudainement, terriblement pertinentes.

Il y a 35 ans, avant mon service militaire, je m’étais porté volontaire comme guide d’un mouvement de jeunesse dans la ville de Karmiel. Un autre guide m’accompagnait, Aviv Kutz, un jeune homme intelligent et doté d’un grand sens de l’humour. Ce 7 octobre, Aviv, sa femme Livnat et leurs trois enfants ont été assassinés par les terroristes du Hamas, dans leur maison du kibboutz de Kfar Aza. Comme tant d’autres parmi nous, j’ai senti le monde s’écrouler.

J’ai brusquement compris qu’après de telles tragédies, la Maison des combattants de ghettos devait être encore plus présente, encore plus active, qu’elle ne l’avait jamais été. Avec Efrat Feldman, instructrice et chanteuse de talent, et Chava Cohen, directrice des événements, nous avons décidé de créer un spectacle traversé par les chants et les récits.

Nous avons immédiatement reçu avec enthousiasme la bénédiction et le soutien chaleureux d’Yigal Cohen, directeur général du musée. Depuis quatre mois, nous nous produisons dans des hôtels et des kibboutzim qui accueillent des milliers d’évacués de guerre du sud et du nord. Le spectacle offre une heure de répit et de consolation aux adultes qui ont été arrachés à leur foyer et à leur triste routine quotidienne. Nous avons intitulé ce spectacle “Il est permis d’aimer” : Chansons, récits et nostalgie (“It is allowed to love” Song Stories and a Longing), – titre extrait de l’un des poèmes de Lea Goldberg, célèbre poétesse dont la vie se mêle aussi au spectacle. Les réactions sont très émouvantes et nous encouragent à continuer, en espérant toutefois que ce cher public rentrera bientôt chez lui, enfin, sain et sauf.

- Pourquoi votre Musée est-il plus particulièrement adressé aux jeunes militaires israéliens ? Que leur dit-il qu’ils ne connaissent déjà ?

Le musée s’adresse aux soldats comme il s’adresse aux lycéens et aux étudiants, partant du principe que les jeunes sont le moteur de la création de l’avenir. Chaque rencontre est unique et différente de la précédente : tout étant singulier pour chaque groupe, que ce fût leur l’état d’esprit, la dynamique avec l’instructeur ou leur niveau de connaissances historiques. L’équipe d’instructeurs, tous aussi professionnels qu’expérimentés, ajuste et adapte chaque session à la spécificité du groupe. Il est essentiel, comme je le mentionnais, qu’il y ait un dialogue, pour qu’émerge à la surface de la vie, de leur vie, ce processus d’éducation, de transmission que la Maison des combattants leur communique, aussi délimité soit-il, en apparence, lors de la visite.

- Miriam Novitch, l’une des fondatrices de ce Musée, qui a connu Yitzhak Katzenelson au camp de Vittel, avait elle-même enterré ses écrits, espérant les retrouver,- si elle lui survivait. Ce qu’elle fit, comme elle retrouva par la suite tous les écrits témoignant de la réalité des juifs de cette période, – que ce fût au ghetto de Varsovie – ou sur tout autre lieu de la planète ! Nombre de ses écrits furent rédigés dans l’urgence par des poètes, des écrivains, des êtres perdus dans la douleur pour des âmes de demain. Sont-ils aujourd’hui lus par un large public ? Et non pas seulement par des historiens ou des chercheurs ? Comment rendre à ses écrits leur urgence ?

Il était très important pour les fondateurs que le Musée porte le nom du poète Itzhak Katzenelson. Katzenelson et son fils aîné, qui s’étaient échappés du ghetto de Varsovie, avaient été déportés au camp de Vittel. En dépit de leurs faux papiers sud-américains, la France, pressée par l’Allemagne, autorisa leur déportation. Début mai 1944, il furent transportés à Drancy, qu’ils quittèrent le 29 avril 1944 pour, dès leur arrivée, les fours crématoires d’Auschwitz (sa femme Chana et ses deux autres fils avaient été assassinés à Treblinka).

Au sein du ghetto de Varsovie, Katzenelson avait enseigné la Bible dans le lycée clandestin créé et maintenu par le mouvement de jeunesse “Dror”. Tous ses élèves devinrent ceux qui, plus tard, menèrent le soulèvement, pour ainsi dire à mains nues. Les rares qui survécurent témoignèrent unanimement de la force et de la motivation que leur admirable professeur leur avait prodiguées. C’est ce que Miriam Novitch nomme, – terme qu’elle a façonné – la “résistance spirituelle”. Car, en effet la résistance ne tient pas seulement sur le soulèvement armé, mais se révèle dans un nombre multiforme d’actes quotidiens. Je voudrais également ajouter que nous devons énormément à Miriam Novitch et à ses infatigables efforts. C’est elle, – elle à l’époque si seule – , qui a réalisé le dernier souhait de Katzenelson, à savoir “de recueillir les larmes du peuple juif”. Ses actions incessantes ont contribué à l’enrichissement de nos archives et, surtout, de l’immense collection d’œuvres d’art qui y est conservée.

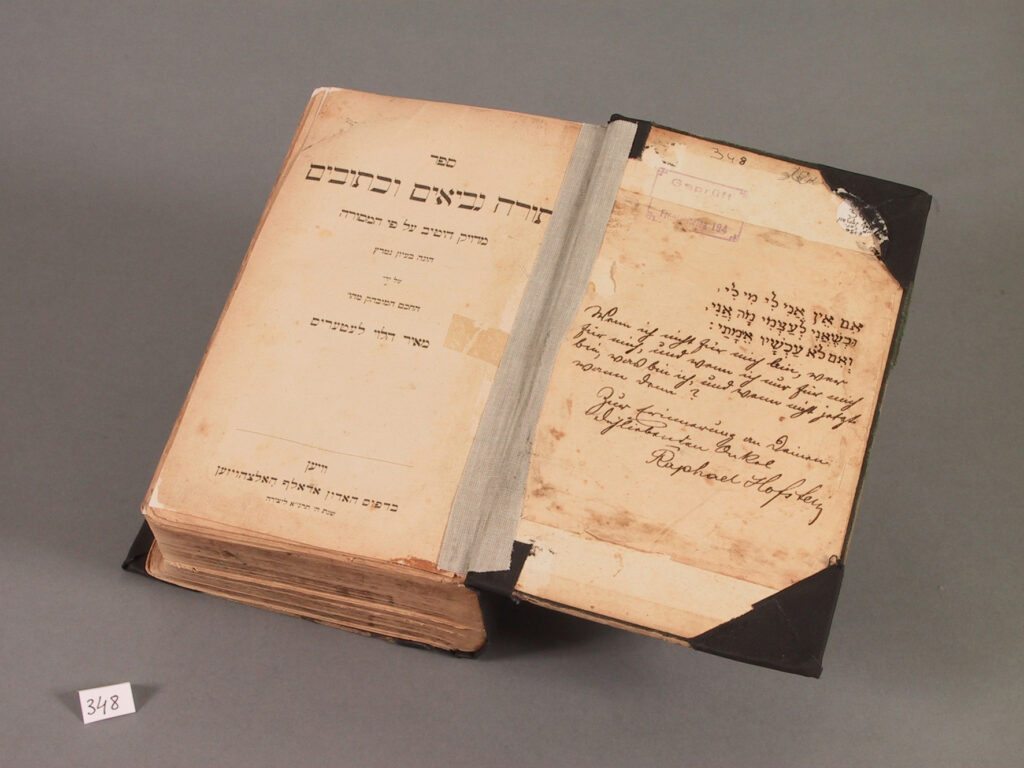

The Ghetto Fighters’house Archives

Malheureusement, les grands écrits d’Itzhak Katzenelson sont fort mal connus. En France, cependant, vous possédez certaines très belles traductions, comme celle du “Chant du peuple juif assassiné”, et le “Journal du camp de Vittel”, mais rien de ses écrits, de toutes ses autres foisonnantes œuvres poétiques[1]. Le plus généralement, ses livres sont uniquement présentés lors d’expositions dans des Musées ou pour des Commémorations annuelles. En dépit des conditions et de son état physique et mental, Katzenelson a continué à enseigner pendant les quelques mois passés à Vittel, rassemblant autour de lui un groupe d’étudiants, prisonniers du camp. Aux côtés de Miriam Novitch se trouvait également Ruth Adler Goldberg, dont la bible servait de support à leurs études. C’est Ruth Adler -Goldberg qui est parvenue à faire passer en contrebande une copie du poème “Chant du peuple juif assassiné”. Le poème, la poignée de la valise dans laquelle il fut caché et la bible sont exposés au sein de notre musée dans le cadre de l’exposition “Yizkor”.

Il y a plusieurs années, la Knesset avait demandé à notre directrice des archives, Anat Bratman – Elhalel, d’emprunter une Bible pour une lecture de Tehilim, ouvrant la cérémonie d’investiture du nouveau gouvernement. Anat avait choisi la Bible d’Adler, la Knesset a alors convié Dani Goldberg, le fils de Ruth, en tant qu’invité d’honneur. Cela fut aussi marquant que terriblement émouvant

- La disparition peu à peu des témoins vivants a-t-elle modifié leur perception ?

C’est évident que cela nous préoccupe. J’appartiens à la génération qui a encore eu l’honneur de guider des survivants à l’intérieur de cette Maison des combattants, d’escorter également des témoins pendant nos voyages d’études en Pologne. Aujourd’hui, nous avons encore deux témoins qui viennent rencontrer des élèves et des soldats au Musée. Je leur envoie, du reste, d’ici, des bénédictions de bonne santé et de longévité. Que ferons-nous après 120 ans ? Nous transmettrons leur témoignage par le biais de films. Leur histoire doit continuer à être entendue. Cependant, c’est vrai hélas que rien ne remplacera l’expérience d’un public qui s’adresse à eux directement à la fin de chaque visite, et qui s’empresse, comme un don de vie, de poser pour une presque traditionnelle photo de groupe.

- Les Archives Ringelblum ont-elles été traduites en hébreu ?

Je serais très heureux que les archives Ringelblum nous parviennent, mais elles sont actuellement conservées à Varsovie. Avec les années, certains segments de ces archives ont été traduits en hébreu et en anglais et ont fait l’objet de nombreuses recherches et de publications. Nous conservons à la Maison des combattants de ghettos une collection complémentaire aux archives Ringelblum, à savoir les archives du Comité national juif (Zydowski Komitet Narodowy), remises par celui qui en avait la charge, le Dr Adolf Abraham Berman. Il s’agit d’une collection riche et fascinante qui, comme celles de Ringelblum, révèle la vie quotidienne du ghetto de Varsovie et relate tout ce qui lui était également extérieur. L’ensemble de la collection Berman a été traduite en hébreu et peut être consultée, accessible au public, sur le site Internet des archives de la Ghetto Fighters’ House (Maison des combattants de ghettos).

- Êtes-vous proche du Musée Polonais qui en conserve l’original (Jewish Historical Institute) ? Comment garder des rapports honnêtes et justes avec les conservateurs et directeurs de ce Musée depuis les lois passées par l’état polonais criminalisant tout chercheur impliquant directement ou indirectement la Pologne dans le meurtre des juifs?

Comment peut-on sérieusement maintenir des relations honnêtes et équitables avec les conservateurs et les directeurs de ce Musée, alors que des lois ont été adoptées par l’État polonais criminalisant les chercheurs interrogeant directement ou indirectement l’implication de la Pologne dans l’assassinat de Juifs ?

Dès la création de la Maison des combattants de ghettos, nous étions très reconnaissants des échanges fructueux et mutuels avec le Musée historique juif de Varsovie en matière d’assistance et de communication de copies de documents d’archives, tant pour la recherche que les expositions. Au cours des dernières années néanmoins, nous avons tenté plusieurs projets de coopération, mais aucun n’a abouti. En tant que chercheur et éducateur, j’estime que ces limitations ou sanctions quant aux recherches historiques sont absolument inacceptables. J’espère sincèrement que quelqu’un reviendra à la raison et annulera cette législation regrettable et dangereuse.

- L’historien, linguiste, Dovid Katz n’a cessé de nous alerter de la profusion de parades ou / et d’érection de statues dans toute l’Europe de l’est glorifiant des anciens génocidaires, – Statue, par exemple, de 7 mètres de haut de Stéphan Bandera à Lviv, en Ukraine (dans ce que fut cette si belle et érudite ville de Lemberg, où naquirent tant de nos grands penseurs, et dont la population juive fut entièrement décimée), Liudas Noreka en Lituanie, Miklos Horthy en Hongrie, le mémorial de Bauska en Lettonie, parmi tant d’autres, … Était-ce le rôle d’un Musée, d’un État, des organisations juives de réagir ?

La montée de la droite conservatrice dans le monde entier devrait tous nous inquiéter. Le fait qu’elle s’accompagne de xénophobie, d’antisémitisme et d’islamophobie ne fait qu’accroître l’inquiétude quant à ce qui nous attend. La pratique de ces États reposant sur la réécriture du passé est pitoyable et très pernicieuse. C’est là mon opinion personnelle même si, bien sûr, ces questions se posent dans nos conversations privées, ici, au musée. Mais nous sommes tous tenus, le musée et moi, à une certaine humilité. Contrairement à Yad Vashem, la Maison des combattants de ghettos n’est pas un institut officiel de l’État. Cela présente des avantages (liberté d’action) et des inconvénients (budget). Je pense qu’il incombe entièrement à l’État d’Israël d’influer sur ces dérives.

- Ces pays ont tous construit leur propre “Musée de l’Holocauste” ? Êtes-vous pour certains en collaboration avec eux ?

Vous avez mentionné plus tôt l’Institut historique juif de Varsovie. Là encore, nous n’avons pour l’instant aucune collaboration avec ces autres musées. Comme dans la vie, pour toute bonne relation, la règle d’or est un jugement éclairé et un réel bon sens.

- Après tant d’années dévouées à ce Musée, comment voyez-vous l’évolution des jeunes au vu de leur histoire et de celle en particulier qui concerne la Maison des combattants de ghettos ? Leur regard a-t-il changé ?

L’Holocauste est un événement unique. Mais depuis, le monde ne s’est pas amélioré. Les faits de génocide au Kosovo, au Rwanda, au Sud-Soudan et dans d’autres lieux peuvent appeler à la comparaison. Selon moi, une telle confrontation a surtout été réfléchie dans les centres de recherches universitaires, bien plus que parmi le grand public israélien.

Et puis, soudain, ont éclaté les tragiques événements du 7 octobre. Soudain, nous avons tous été exposés à des actes d’une brutalité et d’un sadisme innommables perpétrés par des membres du Hamas. Les témoignages intenables des survivants du massacre nous ont ramenés aux récits de l’Holocauste, comme si nous étions revenus 80 ans en arrière, en ce temps où la vie juive était déchue, confisquée puis piétinée.

J’ai récemment donné cours à un groupe d’enseignants d’une école située à la frontière du Liban, évacuée en raison de la guerre et temporairement installée dans notre musée. Lors du discours d’ouverture de l’exposition sur le ghetto de Varsovie, je leur ai demandé de faire connaître leur nom et de nous parler d’un événement positif et optimiste, survenu depuis le 7 octobre. Cela les a surpris, mais ils se sont prêtés au jeu. Et chacun y est parvenu. Ensuite, j’ai parlé de l’exposition et fait le récit du profond désespoir des habitants du ghetto après la grande déportation vers Treblinka au cours de l’été 1942. J’ai décrit la force mentale et l’espoir des membres de l’Organisation juive de combat (Z.O.B.) pour sortir de ces bas-fonds et mener le ghetto jusqu’au soulèvement. Lorsque nous avons visité l’exposition “Justes parmi les nations”, je leur ai raconté la grande histoire du sauvetage de mon oncle Alexandre (le frère de ma grand-mère), de sa femme et de ses deux petites filles dans le Paris occupé. Je les ai invités à s’inspirer de ces deux histoires pour comprendre la valeur de la responsabilité personnelle.

De la même façon que ces professeurs enseignent à leurs élèves que la réussite dépend de l’investissement et de la somme de travail que l’on y engage, nous sommes aujourd’hui devant un terrible défi : celui de trouver la force de dévier, de transformer notre colère, notre amère déception, nos angoisses – légitimes et compréhensibles – de transmuer suffisamment ces redoutables sentiments pour trouver le chemin responsable vers ce qui est juste, et nous demander dans quel type de société nous voudrions, prochainement, une fois cette guerre terminée, vivre à nouveau ?

Je laisse cette question ouverte, mais ma réponse est claire : une société libérale, tolérante et pleine d’humanité.

Site web du musée – https://www.gfh.org.il/eng

“Oh qui nous pleurera ? Qui érigera un monument commémoratif pour nous ? Qui racontera au monde l’histoire de notre grand peuple, les Lévites des nations, fils des Prophètes !” se lamentait toute une nation par la voix d’Yitskhak Katzenelson.

Merci au Musée des Combattants de ghettos pour l’obstination de bravoure et d’humanité dont vous n’avez jamais cessé de faire preuve. Un proverbe yiddish dit que “tous les juifs sont frères, mais que chacun est un Seigneur”. Merci à vous, Lior Inbar, d’avoir accepté cette interview et de nous insuffler aujourd’hui, dans cette folle détresse, un peu de votre “flamme infatigablement incandescente”.

***

Photos appendix

- The Ghetto Fighters’ House

- The Treblinka camp model, made by Jakow Wiernik, The Ghetto Fighters’ House

- Lior Inbar

- Efrat Feldman and Lior Inbar, Kibbutz Beit Alfa, November 2023

- Efrat Feldman sing Shaul Tchernichovsky’s poem “I believe”, Kibbutz Ein Harod Meuad, January 2024

- The team of the performance “It is allowed to love”: Efrat Feldman, Hava Cohen and Lior Inabr, Tiberias, January 2024

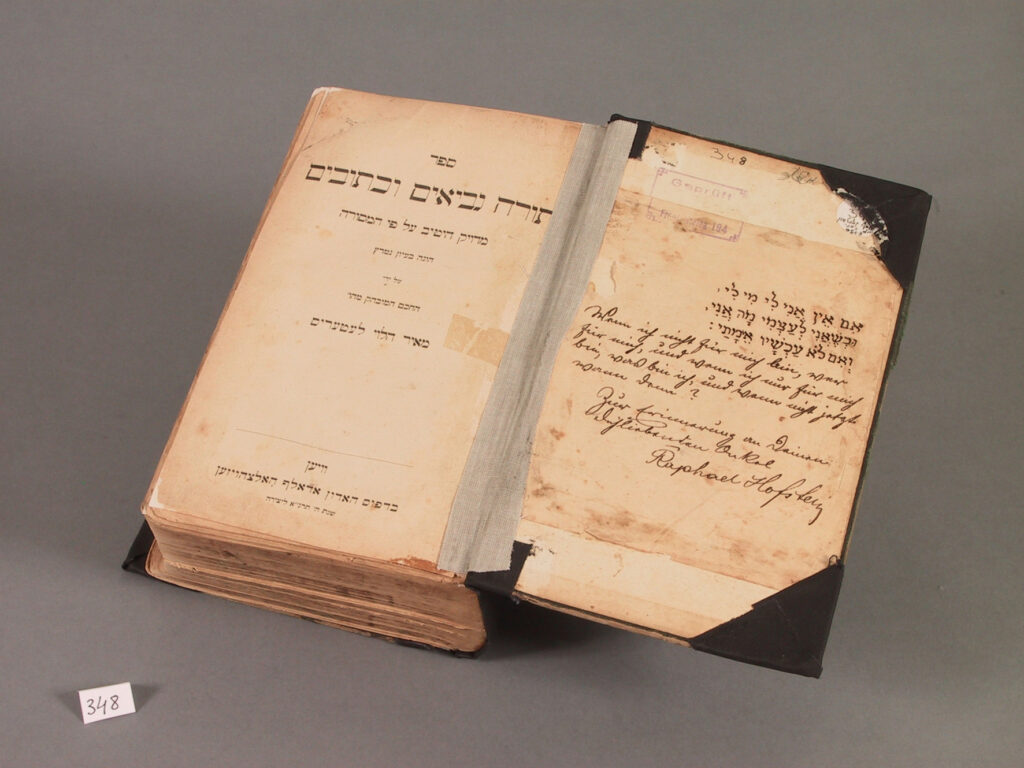

- 7. Bible from Vittel camp in France which was belong to Ruth Adler-Goldberg, The Ghetto Fighters’ House Archives.

- Itzhak Katzenelson

- Ruth Adler-Goldberg

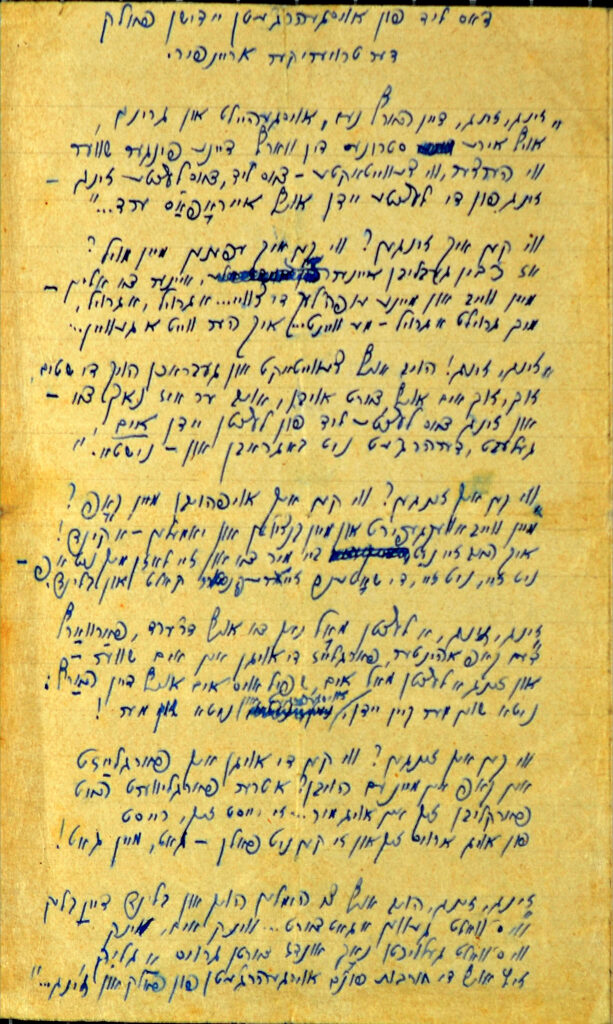

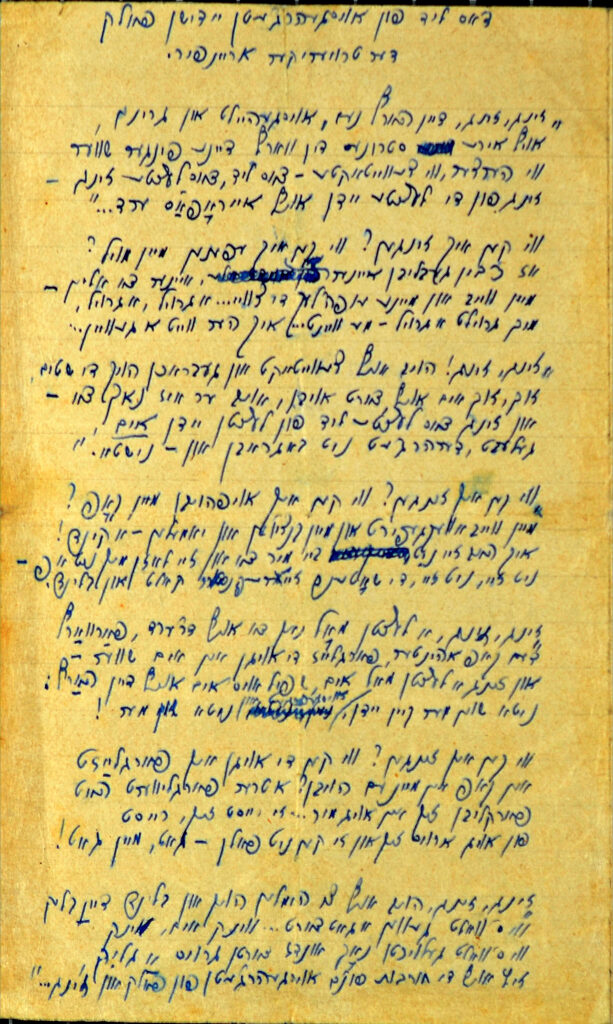

- The first page of the poem “”The song of the massacred Jewish People” by Itzhak Katzenelson

Notes

[1] Yitskhok Katzenelson, “Le Chant du peuple juif assassiné”, Ed. Zulma, Traduit du yiddish en français par Batia Baum, préfacé par Rachel Ertel. Cette élégie déchirante est un chef d’œuvre absolu pour sa force, sa beauté, son humanité, et ce qu’il nous transmet de nécessaire vaillance, sans ciller, face au diable. Yitskhok Katzenelson était un conteur, un dramaturge, un traducteur et surtout un poète. Il laisse une œuvre foisonnante dans ses deux langues juives. Peu hélas, très peu a été traduit. Ardent sioniste, profondément inspiré par les travaillistes juifs et les mouvements de jeunes pionniers sionistes-socialistes Dror (ou Farayhayt-Dror, “Liberté”) et du Hekhkaloutz (“Le Pionnier”), il se démarquait de ses compères intellectuels en défendant la langue yiddish et sa littérature comme marque de cohésion du peuple juif. La version originale du “Journal du camp de Vittel” publié pour la première fois en hébreu (récemment publié en France aux Éditions Calmann-Lévy) se trouve à la Maison des combattants.

Entretien mené par Daniella Pinkstein

Version anglaise

Interview with Lior Inbar, historian and archivist at the Beit Lohamei Haghetaot Museum (Ghetto Fighters’ House)

By Daniella Pinkstein

“To enlighten the world the must be

a flame burning within you”

Miriam Novitch, Member of Kibbutz (1950)

Western Galilee, February 19th, 2024

On my way…

I had the feeling of a journey, in a single day, a long but accelerated expedition. Although by my reckoning, the Museum was only a few kilometers from my home. I had decided to take the bus, or rather buses, to get to the Museum. I didn’t know (how could I forget?) that Israeli buses roll over their wheels, and that you’re more shaken up than in Satanas and Diabolo’s Demona. Terrible heat, stony road, the first bus indicates a stop, I get off. And I wait! Nowhere, in the middle of a road that looks like a path trodden by crazy trucks. I wait again, unable to identify where the hell I am or what I’m seeing. The bus, after a few others that don’t stop, comes; I get on. Who knows if I’m on the right one. Screaming, because I’ve noticed that Israeli bus drivers never inform you, they yell at you! I get off. Likewise, in the middle of what seems to me like nowhere. In the distance, a field, a fence. A large building. This must be it. I’m in Galilee, in Western Galilee. The landscape seems to expand, to breathe, it stretches as if under the effect of perpetual first rays of light.

The Museum stands before me, vast, infinite. I don’t understand how – but it’s always like this in Israel – you can go from one state to another so quickly, from one vision to its opposite, from one perspective to such a vast horizon so suddenly. For, right now, what stands before me is unlike any other landscape.

I’m not going to talk about the Museum, which Lior Inbar, who has been working there for 20 years, will do with great knowledge and intelligence, I just want to add before I start this interview, how this Museum has no equal. Having visited a number of Holocaust memorial sites, including of course Yad Vashem, dragged at first by my trembling father, then alone, trembling in my turn, I had the great emotion of leaving Beit Lohamei, my soul full, my eyes dazzled with pride and hope. On the terrace deliberately built above the Museum, overlooking the whole of Galilée and opening onto the Kibbutz, I saw clearly, without the slightest shadow, on that infinite horizon, that extraordinary Jewish life. Irreducible.

Today is October 7. Like every day since October 7. What the “House of Ghetto Fighters” has passed on, and never ceased to want to pass on, must be perpetuated. Today again. So that tomorrow’s days can tick by, build up minute by minute, regaining their rhythm until the clear rays of the next Shabbat.

– First of all, can you explain in a few words what makes your Museum so special? And what makes it so different from Yad Vashem?

The Ghetto Fighters’ House was unique from its very first day: it was founded in April 1949 when the Kibbutz Lohaemi HaGeta’ot settled in Western Galilee. 150 young Holocaust survivors gathered to build a community and a future for their children while also establishing an institute dedicated to the commemoration, documentation, and education of the Holocaust. The inauguration ceremony of the kibbutz was also the memorial assembly marking six years since the outbreak of the Warsaw ghetto uprising. Several of the kibbutz founders were among the leaders of the uprising, including the couple Zivia Lubetkin & Yitzhak (Antek) Zukerman. Establishing the GFH museum was an impressive and influential act of pioneering. They didn’t wait for the young state of Israel to take responsibility for the commemoration of the Holocaust but did it themselves. It took a few years until the state established the “Yad Vashem” Institute in Jerusalem. The founders’ decision to name the Museum “House” isn’t just a title but something much more fundamental: they wished to give the visitors a warm sense of familiarity and closeness during their visit. The museum holds themed exhibitions that invite and inspire the visitor to a dialogue, allowing meaningful educational discussion in each one of them. This is how we perceive our mission as the successors of the founders and it is what sets us apart from any other institution, including Yad Vashem.

What is your role in this Museum? Has it changed over the years and with your experience?

By training, I’m a history and citizenship high school teacher. I began my work at the Ghetto Fighters’ House as an instructor almost twenty years ago. After completing my master’s degree in history, I joined the archive team as a researcher and throughout the years I have published several academic articles that are based on the treasures that can be found in our archive. I was also the editor and director for several years of the annual commemoration assembly during the Holocaust Remembrance Day and I managed the Scholarship Research Fund of the Museum. For the last several years I have been directing the teacher training department. Last year I started a PhD study in Haifa University, my research focus on the kibbutzim movements after the Yom Kippur 1973 war. Until Saturday 7.10 that war was the most tragic event in the kibbutzim history. Sadly, my research became even more relevant.

35 years ago, before my army service I volunteered as a youth movement guide in the city of Karmiel. Another guide there was Aviv Kutz, a smart young man with a great sense of humor. On 7.10 , Aviv, his wife Livnat and their 3 children’s were murdered by Hamas terrorists in their home in Kibbutz Kfar Aza. Like many others I felt the world turn apart. I realized that after such a large scale of tragic events, the Ghetto Fighters’ House must do more than what has been done until now: Together with Efrat Feldman who is an instructor and a wonderful singer, and Chava Cohen, the events director, we created a performance of songs and stories. Gladly we received the bless and warm support of Yigal Cohen, the CEO of the museum. For the last four months, we have been appearing entirely voluntarily in hotels and Kibbutzim that host thousands of war evacuees from the south and north. The performance offers an hour of respite and consolation to adults who have been torn from their homes and daily routines. We called the performance “It is allowed to love“: Songs, Stories and a Longing” which is a quote from one of Lea Goldberg’s poems, a well-known poet whose life story is woven into the performance. The responses are supportive, and heart-touching and I hope that this dear audience will soon return home safely.

– Why is your museum particularly aimed at young Israeli soldiers? What does it tell them that they don’t already know?

The Museum addresses soldiers just as it addresses high school pupils and university students, based on the view that young people are the force driving the creation of the future. Each meeting with such a group in the Museum’s exhibitions is unique and different from the previous one: the mood with which the group arrives, the dynamics with the instructor, and the level of historical knowledge that the group brings. The team of instructors who are all highly professional and experienced adjust and fit each instructing session with the specific group. I mentioned earlier our wish to form a dialogue during the tours – the meaning of such a dialogue and the insights that emerge on the group’s part about their lives today, is that the group had gone through a significant educational process, albeit a small one, during their visit at the museum.

– Miriam Novitch, one of the Museum’s founders, who had known Itzhak Katzenelsonin the Vittel camp before he was deported, had buried his writings herself, hoping to find them – if she survived him. Which she did, just as she subsequently found all the writings bearing witness to the reality of the Jews of that period, – whether in the Warsaw ghetto – or anywhere else on the planet! Many of his writings were penned in a hurry by poets, writers, people lost in pain for the souls of tomorrow.

– Are they read today by a wide public? And not just historians and researchers?

– How can we restore the urgency of those writings?

The decision of the founders to name the museum after the educator and poet Itzhak Katzenelson was highly significant and important. Katzenelson and his eldest son were deported from Vitel Camp to Auschwitz where they were murdered (his wife Chana and his two other sons were murdered in Treblinka). Earlier, in Warsaw ghetto, Katzenelson served as a bible teacher at the underground gymnasium organized by the “Dror” youth movement. His pupils were later those who led the uprising against the Nazi occupation. Those who survived testified how they were empowered and motivated by their much-admired teacher. Miriam Novitch coined the term “Spiritual Resistance” which meant exactly that: the resistance was not reflected only in the armed uprising but in a wide variety of everyday acts. I would like to add that we owe a lot to Miriam Novitch and her efforts. The fact that she had fulfilled Katzenelson’s last wish “To collect the tears of the Jewish people”, contributed immensely to the body of materials in our archive and more than all to the rich art collection kept in it.

Unfortunately, the canonical texts written by Itzhak Katzenelson are less known today. They always have a representation in the Museum’s exhibitions and the annual memorial assembly but nothing much beyond that. Katzenelson continued teaching during his months in Vitel, gathering around him a group of students, prisoners of the camp. Next to Miriam Novitch was also Ruth Adler Goldberg whose bible served as the learning material of their studies. Adler was the one who smuggled and brought to Mandatory Eretz Israel a copy of Katzenelson’s poem “The Song of the Massacred Jewish People”. The song along with the suitcase handle in which it was smuggled and the bible, are exhibited in the museum at the “Yizkor” exhibition. Several years ago, the archive director, Anat Bratman – Elhalel received a request from the Knesset of Israel to loan the bible for a Tehilim reading during the New Government’s swearing-in ceremony. Anat chose Adler’s bible and the Knesset invited Dani Goldberg, Ruth’s son to the ceremony as a guest of honor. This was an important and touching closure.

– Has the gradual disappearance of living witnesses altered their perception?

This is certainly something that occupies us. I belong to the generation that still had the honor to guide Holocaust survivors through the Museum’s exhibition and escort witnesses during pupils’ voyages to Poland. As for today, we still have two witnesses coming to meet students and soldiers at the museum. I’m sending them from here too blessings of good health and longevity. What will we do after 120 years? We will show their testimony by film. Their story will continue to be heard but nothing can replace the experience of an audience asking questions at the end of these sessions and the traditional group photo.

– Have the Ringelblum Archives been translated into Hebrew?

I would be more than happy if the Ringelblum archive would find its way to us, but it is kept in Warsaw. Throughout the years sections of it were translated into Hebrew & English and it had been the subject of research and publications. We hold at the Ghetto Fighters’ House a complementary collection to the Ringelblum archive, which is the archive of the National Jewish Committee (Zydowski Komitet Narodowy) that was donated by the man who directed it – Dr. Adolf – Abraham Berman. This is a rich and fascinating collection, which, like Ringelblum, reveals the everyday life in the Warszawa ghetto and what happened beyond the ghetto’s walls. The entire Berman collection was translated into Hebrew and can be found, accessible to the public on the Ghetto Fighters’ House archives’ website.

– Are you close to the Polish Museum (Jewish Historical Institute) that preserves the original?

How can you maintain honest and fair relations with the curators and directors of this Museum since the laws passed by the Polish state criminalize any researcher directly or indirectly implicating Poland in the murder of Jews?

From the very early days of the Ghetto Fighter’s House, we have been grateful for a mutual relationship with the Jewish Historical Museum of assistance and communication by exchanging copies of archive materials for research and exhibitions. During the last several years we have had several plans of cooperation, but they didn’t come to fruition. As a researcher and educator, I perceive any limitation or sanctioning of free research as unacceptable and wrong. I truly hope that someone there will come to his senses and cancel this unfortunate and dangerous legislation.

– Historian and linguist Dovid Katz has constantly alerted us to the profusion of parades and/or statues erected throughout Eastern Europe glorifying former genocidaires – a 7-meter-high statue of Stefan Bandera in Lviv, for example, in Ukraine (in what was once the beautiful and erudite town of Lemberg, the birthplace of so many of our great thinkers, and whose Jewish population was completely decimated), Liudas Noreka in Lithuania, Miklos Horthy in Hungary, the Bauska memorial in Latvia, among many others, … Was it the role of a Museum, a State or Jewish organizations to react?

The strengthening of the conservative Right around the world should worry us all. The fact that this is accompanied by xenophobia, Antisemitism and Islamophobia only heightens the worry about what lies ahead. The practice of re-writing the past of these states is pathetic and dangerous. I’m expressing here my personal opinion and of course these issues surface from time to time in our internal conversation at the museum. But we, the museum and I, are required to hold here a measure of humility. As opposed to Yad Vashem, the Ghetto Fighters’ House is not an official institute of the State. This has advantages (freedom of action) and disadvantages (budget). I believe it is entirely the responsibility of the State of Israel to deal with these processes.

- As most of those countries built their own “Holocaust Museum, are some of you in collaboration with them?

You mentioned earlier the Jewish Historical Institute in Warszawa, here too we do not have at the moment any collaborations with these museums. As with any relationship in life, the rule of thumb is sound judgment and common sense.

– After so many years in this Museum, how do you see the evolution of young people in the light of their history? Has their opinion, the way they look at it changed?

The Holocaust was a unique and one-time event, but the world did not get better after it: events of genocide in Kosovo, Rwanda, South Sudan, and other places called for comparison. In my estimation, this comparison has been carried out more in research and inside the academia and less among the public in Israel. Then the terrible events of 7/10 took place, and we were all exposed to the acts of brutality and monstrous sadism of the members of the Hamas organization. The difficult testimonies of the survivors of the massacre brought back the stories of the Holocaust to the public discourse. There is a saying that we went back 80 years to the days when Jewish life was forfeited and trampled.

I recently instructed a group of teachers from a school on the border with Lebanon which was evacuated due to the war and relocated temporarily in our museum. During the opening talk at the Warsaw ghetto exhibition, I asked people to say their names and talk about one good optimistic event that happened to him or her since 7/10. It surprised them but they went along, and each one found such an event. Following that, I began talking about the exhibition and the deep desperation of the ghetto residents after the great deportation to Treblinka in the summer of 1942. I described the mental strength and the hope of the members of the Jewish Combat Organization (Z.O.B) to rise from these shallows and lead the ghetto to an uprising. When we walked through the Righteous Among the Nations exhibit, I told them about the great rescue story of my uncle Alexander (my grandmother’s brother), his wife, and two little daughters in occupied Paris. From these two stories, I invited them to draw their understanding of the value of personal responsibility. Just as they explain to their students that being successful depends on investment and hard work, so we are today challenged to transform the feelings of anger, disappointment, and anxiety which is legitimate and understandable, yet it is our responsibility to find what is good and ask ourselves in what kind of society we want to live in after the war is over? I left this question open, yet my answer is clear: a liberal, tolerant, and compassionate society.

***

Museum website – https://www.gfh.org.il/eng

“Oh who will mourn us? Who will erect a memorial for us? Who will tell the world the story of our great people, the Levites of the nations, sons of the Prophets!” lamented an entire nation through the voice of Yitskhak Katzenelson.

Thank you to the House of the Beit Lohameik Haghetaot, Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum, for your persistent bravery and humanity. A Yiddish proverb says that “all Jews are brothers, but each one is a Lord”. Thank you, Lior Inbar, for accepting this interview and for breathing into us today, in this mad distress, a little of your “tirelessly incandescent flame”.

Photos appendix

- The Ghetto Fighters’ House

- The Treblinka camp model, made by Jakow Wiernik, The Ghetto Fighters’ House

- Lior Inbar

- Efrat Feldman and Lior Inbar, Kibbutz Beit Alfa, November 2023

- Efrat Feldman sing Shaul Tchernichovsky’s poem “I believe”, Kibbutz Ein Harod Meuad, January 2024

- The team of the performance “It is allowed to love”: Efrat Feldman, Hava Cohen and Lior Inabr, Tiberias, January 2024

- 7. Bible from Vittel camp in France which was belong to Ruth Adler-Goldberg, The Ghetto Fighters’ House Archives.

- Itzhak Katzenelson

- Ruth Adler-Goldberg

- The first page of the poem “”The song of the massacred Jewish People” by Itzhak Katzenelson

Entretien mené par Daniella Pinkstein

Poster un Commentaire